The 14 Year Road Trip to Discovery

Share

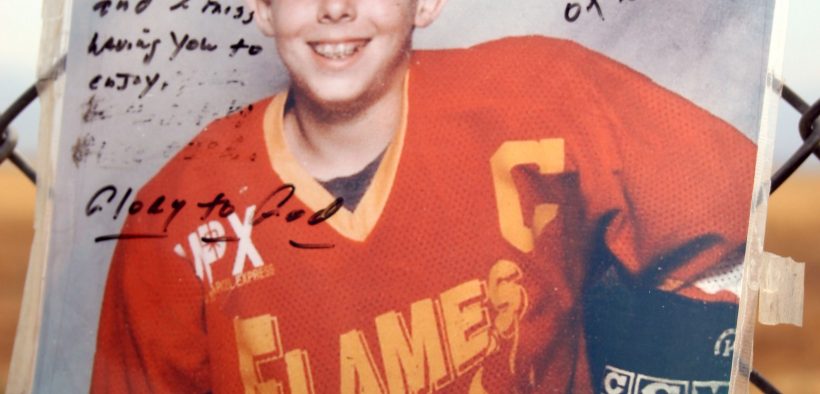

What ideally started out as a single journal article quickly became a turning point in Dr. Robert M. Bednar’s career as both a scholar and photographer. In Dr. Bednar’s sabbatical inspired paper titled “Moving Pictures: The Lives of Photographs of the Dead at Roadside Car Crash Shrines”, he discusses his deep interest in how pictures move in the world, how they move people, and most importantly, “how moving pictures intersect with moving bodies, cars, and objects in the landscapes of automobility to move people in particular ways”.

Since graduate school, Dr. Bednar’s, associate professor of communication studies, research has focused primarily on the American West and Southwest. Since the startup of his project in 2003, Dr. Bednar has done ongoing fieldwork in central Texas for 14 years, while also accomplishing longer field research throughout the American Southwest every few years. When asked about his lengthy travels, Dr. Bednar reported that the longest single fieldwork trip that he had taken was in 2006, when he and his family traveled 6 states, studying roadside trauma shrines for a total of 6 consecutive weeks!

“I was first drawn to this project because I had seen roadside car crash shrines on the roadside throughout my travels in the Southwest and was curious about what they were doing on the roadside”, he stated.

He further mentions that ,in the beginning of his research, his main focus was on roadside trauma shrines’ purposes in terms of why they were where they were, but moreso how his research evolved his interest in what culture work these shrines were doing in terms of what they do to make strangers driving by them aware of them- referring to these shrines as “a materialization of the trauma of living in a car culture”.

Dr. Bednar’s larger argument, found in his upcoming book, is that a roadside trauma shrine works by “replacing the interrupted life of a crash victim with a new virtual life that is allowed to take its course as it was expected to before it was interrupted by the crash”. In this way, he further explains that these shrines are replacing the victim in ‘social space’ as well as compensating for ‘the displaced victim’s lost future as a social entity’.

While the victim’s life can no longer go on, the shrine serves a theoretical purpose of carrying on what the victim can no longer live; birthdays, anniversaries, holidays, etc.

“And as it does, along with other shrines, it opens up a space for a collective sensing of the fact that the trauma of the many individual car crashes every day in America add up to a cultural trauma” Bednar said.

Notably, Dr. Bednar admitted that he did not think this project would have occurred if it were not for his outright love for being a photographer. His interest in how people think about and picture landscape as well as ‘how ordinary people make space for themselves in certain places’ has most definitely played a key role in the inspiration of this long term project. Furthermore, he goes on to explain how this project has not only opened his eyes to how these shrines work and its counterparts associated, but also how this project yet alone has aided his photography by the means of developing new skills and practices as a photographer.

“It has challenged me to develop an approach to photographing different places that are systematic and disciplined enough so I can compare sites over space and time while also still being flexible and sensitive enough to deal with the fact that each shrine is radically different from other shrines and can be radically different from itself over time,” Bednar said.

With great challenge, he has learned to “tune into the most minute detail but also tune into large-scale patterns, and the way these things can be photographed and the ways they resist being photographed.”

In the last 14 years, Dr. Bednar has captured over 7,000 photographs of roadside shrines, explicitly revisiting and re-photographing many of them in central Texas and in northern New Mexico, sometimes taking more photographs of some sites than others.

“In some cases, I have hundreds of photographs of the same site over the course of that 14-year period, which has allowed me to build in a longitudinal dimension to my study, and has become central to how I see shrines working as a cultural form not only in particular places but also over time,” Bednar said.

In witnessing how these roadside trauma shrines show society that the victim’s’ loss is not only their loss but that of our culture’s, Dr. Bednar has come to know how trauma is in fact a vital teacher, “not a teacher you want to have, but one you need to learn from.”