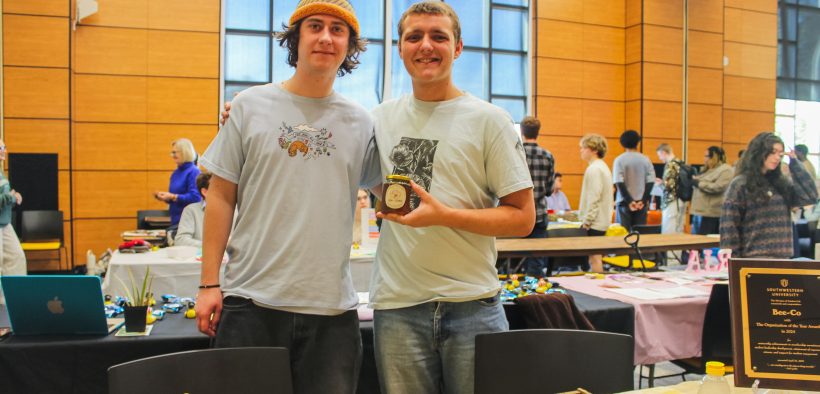

Whats the Buzz: The Bee Club

Share

I hear a faint buzzing sound, but what could it be? Exactly—bees! Southwestern University has its very own beekeeping club! However, the Southwestern Bee Club is in transition. Its founder, Layla Hoffen, graduates this semester. Congrats! But the hives are being relocated from the nature preserve to a plot behind the cemetery. It’s more space, more wildflowers, and arguably a better habitat. But relocation is stressful for a bee colony, and the students who care for them are feeling it too.

Layla Hoffen started the Bee Club in 2023. She did have some institutional backing, but more importantly, years of hands-on training working with bees. She also upholds the conviction that students need. This club is where students actively took initiatives that started traditions we hope to see year after year. Beekeeping is a different kind of access to the environment than most clubs on college campuses offer. As the learning and engagement are not through textbooks or lectures, but through direct, tactile relationships with the cute, friendly insects. Sustainability and environmentalism are often taught as abstract concepts, such as carbon footprint, policy frameworks, and distant crises. Layla wanted to make them tactile.

Layla founded the Bee Club not to save bees, but to help students sit still with them. Her premise was simple: when you understand a creature, you stop fearing it. When you stop fearing it, you become willing to protect it. She wanted students to hold a frame of brood (the honeycomb) in their gloved hands and realize that this is what we’re trying to save. Not an idea. A living thing.

The club began with a handful of inspired students, with limited supplies. Today, it has seventy members, forty-four of whom are trained, active beekeepers. That incredible growth did not happen because beekeeping is glamorous. It happened because students kept showing up. The club promoted a relaxed, nurturing community where students found love for a new passion.

For me, it all began when a bumblebee landed on me. As the weather defrosted these past weeks, I found myself outside. When a bumblebee landed on my knee and stayed. Most people would have panicked. But Layla Hoffen had taught me something: take a step back, reflect, and listen more intentionally. Recollect yourself. Recognize that connection with nature is not something you can appreciate without understanding it’s something you receive.

And yet most of us only think about bees when someone asks if we like jazz. They are fuzzy, sociable, and deceptively complex creatures. They live in matriarchal but rigidly hierarchical colonies, each member performing a specialized function. The queen is protected her entire life. The weaker ones starve alone. Workers make three-mile flights to collect nectar, then return to feed larvae. Builders repair the honeycomb. Guards defend against birds and pests. The colony depends on every bee knowing its role.

On Southwestern’s campus, our bees live in wooden hives with wax-based foundations. Inside, they construct the hexagonal nests we recognize from textbooks and honey jars. But the bees themselves are not textbook creatures. They are responsive, communicative, and capable of teaching lessons that no classroom can.

From Layla’s words, in a sense, “Through beekeeping, I gained a perspective on environmentalism I couldn’t have accessed through coursework alone. People ask me how I continue this work when I get stung frequently, or why I assume the risk at all. The answer is simple: beekeeping is not a conditional relationship. It is not transactional. I do not tend bees so that they will reward me with honey or refrain from stinging. I tend bees because stewardship is not ownership. A keeper does not claim dominion over other beings. A keeper is entrusted with their care, and in that trust learns to work reciprocally, symbiotically, with mutual understanding as the only goal.”

This distinction, stewardship versus ownership, reshaped the way she moves through the worldas she no longer seeks nature as a refuge from human life. Instead, she continued, “I find myself wanting to protect and advocate for nature itself, not for my own sake but for its own. Being outdoors is no longer just solace. It is a responsibility. And that responsibility is rooted in knowing and loving something well.”

Aware of this call to action, Layla acknowledges most people’s hesitations. “When my bees sting me, I never blame them. A sting is not an attack; it is feedback. It means I miscommunicated. I failed to read their cues. So I step back, reflect, and listen more intentionally. True connection requires mutual understanding. Blame is what we reach for when we cannot accept that we were the ones not paying attention.”

Lainie Siegel ‘27 said that Layla, as a leader in the club, is a nice, calm presence who is always so positive and a great teacher. Lainie continues to describe her connection to the hive in gendered and political terms. She loves that everyone listens to the queen. She loves that every bee contributes what it is supposed to contribute. In the world outside the apiary, she sees dysfunction, inefficiency, and hierarchies that benefit the wrong people. But inside the hive, function follows form. The colony thrives because each member performs their role without extraction, without exploitation, and all women are in positions of power. Lainie finds empowerment in that model andwishes more human systems worked like bees.

Another member’s favorite memory is not quiet or meditative. It is loud, industrial, almost the complete opposite of nature. “During a trip to the Round Rock Honey facility, we watched our club’s honey get processed: frames lowered into place, locked in, spun at high velocity until centrifugal force separated the honey from the wax. He described it as alchemy. Our honey, which we had lifted and checked and worried over for months, transformed into something shelf-stable, recognizable, finished.” There is satisfaction in that transformation, exhibiting evidence that attention, sustained over time yields tangible results. These are not identical experiences. One is philosophical. One is tactile. Both are reasons people stay.

Joey DeLuna, the club’s director of outreach, came to beekeeping with a connection to monarch butterflies. His environmental studies class examined metamorphosis, the exchange of comfortable stagnation for radical transformation. The club taught him that this exchange is not optional. Time moves on. Seasons change. You cannot remain who you were.

“Bees still need their weekly check,” he said. “Even if it’s not sunny. Even if you failed a class, or got broken up with, even if everything else is falling apart, the bees still need you to show up.”

The club organizes itself around this principle. Fall brings educational meetings in the library: brood patterns, pest management, and winterization protocols. Spring brings hands-on inspections, requeening decisions, and habitat preparation. There are also honey extractions, wax rendering, and candle-making workshops. The rhythm is liturgical. It repeats whether you are ready or not, and the rotation does more than prepare students for beekeeping. It prepares you for continuity itself. We do not know what the future holds for the bees or for us. But we can do what we can, while we can.

What the Bee Club offers is difficult to quantify. It is not résumé padding, though leadership experience and technical skills are real outcomes. It is not therapy, though members consistently report that their worries recede when they suit up. It is not traditional environmental activism, though seventy students now move through campus with different eyes, noticing flowering plants, understanding pesticides, gaining the skill of holding hundreds of living creatures in their gloved hands, and being able to return them unharmed. The club offers competence in a skill few people possess. It offers a community organized around shared attention rather than shared consumption. It offers evidence that your labor can sustain something beyond yourself. You watch honey supers fill across a semester and know that you contributed to that abundance. You learn that stewardship is ultimately more gratifying than ownership. The club will teach you the rest.

The bees are moving. The founder is graduating. The club is, by any objective measure, in flux. But the hives still need checking. The work continues because that is what work does. It outlasts the people who begin it.Seventy students learned to recognize pollinators. Forty-four can perform hive checks independently. Dozens more attended candle-making workshops, honey-tastings, and informational sessions. These students now understand that environmental justice is not always dramatic.

You do not need experience. You do not need to be an environmental studies major. You do not need to be unafraid of insects, or comfortable outdoors, or certain that this is something you want to commit to. You only need to show up.

LINKS

Bee club instragram: @beesouthwestern

Bee Club Main Website: BEE-Co Main Website

Bee Keeping at Southwestern With Layla Hoffen: SU spotlight video