Southwestern Builds America: How the V-12 Program Saved SU

Share

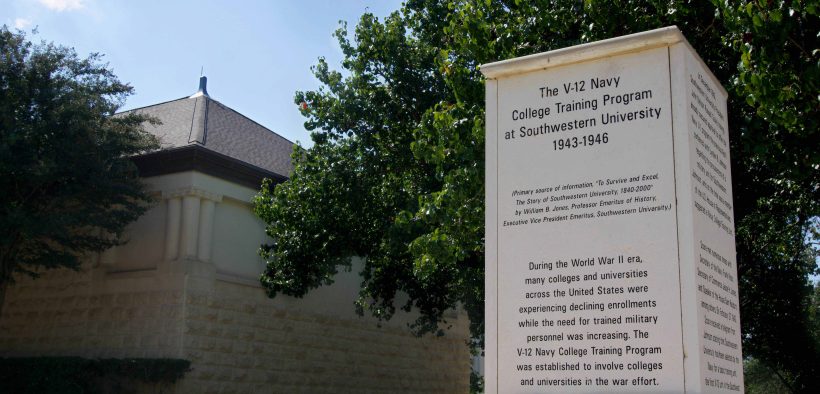

If you’re like me, perhaps on your way back from a workout in the Robertson Gym, or leaving a class in Olin, you may have noticed a pristine stone obelisk surrounded by flowers. Perhaps you’ve read its inscription, dedicating itself to those who participated in the wartime V-12 Program–a program that saved Southwestern University when it was struggling.

On a sunny day in Austin, Texas, in 1943, SU President John Nelson Russell Score walked into the office of an up-and-coming senator, and future president of the United States, Lyndon Baines Johnson. Score hoped to convey the slumping student numbers at SU, which had suffered since the Selective Training and Service Act was passed. Signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940, the Burke-Wadsworth Act required men aged 21-35 to register with draft boards. An internal Southwestern report, issued in November of 1941, indicated that this resulted in a decline of students by about 12%.

Johnson, hoping to mitigate this decline, agreed to give Score ten minutes; however, the two men talked for two and a half hours. It’s impossible to say exactly what occurred during this meeting, but the result is the same–Southwestern University became one of 131 colleges and universities that participated in the V-12 Program. The V-12 Program, initiated by the U.S. Military, provided education to soldiers and ensured the United States had no shortage of college-educated officers. Not only did Southwestern’s V-12 program play a significant role in churning out officers for the war effort, but numerous participants and organizers of the program argued that the V-12 program helped Southwestern survive as an institution.

Johnson had a connection to Southwestern University before his conversation with Score. In 1937, in the years leading up to World War II, he accepted a role on the Council of Navy Affairs. A year later, a woman named Pearl Neas wrote a letter of support to Johnson. Neas was a registrar at Southwestern University and would continue correspondence with him over the years. His wife, Claudia Alta “Lady Bird” Johnson, also maintained correspondence with Neas, and their friendship culminated in the Johnsons allowing the university to broadcast a program through their radio station, K-LBJ. This program, entitled “Southwestern Builds Americans,” was broadcast from what is now the Roy and Lillie Cullen Building. This relationship would be key in setting the conditions for establishing the V-12 program. Looking back later, Johnson wrote to Neas: “Dear Pearl, in looking back over my years in public life, I realize that I am indebted to many people; however, I can’t think of anyone who has been more consistent and more conscientious in making my progress possible than you. I don’t even know how to express my gratitude.”

Marjorie Beech, a Southwestern faculty member at the time, would characterize Johnson’s contribution as such: “Congressman Lyndon Johnson had a very real part, an admirable part in obtaining what was eventually the largest V-12 unit in the nation, that is west of the Mississippi…Southwestern was itself going to suffer as many colleges were doing by the loss of its young men, because one by two by three they were enlisting or being drafted, and most of them didn’t wait to be drafted; they went ahead and enlisted. And as some of our best and brightest young men were leaving, their girlfriends followed suit. When their boyfriends left or were transferred, some of them were leaving, so action was demanded.”

Recruits of the V-12 program endured a rigorous regimen far more militant than your average freshman might face. “Six-thirty back to seven, we had to shave and shower…breakfast at eight in the mess hall. We were given…an hour to eat…and then at nine o’clock you started classes. We went to class all day long;…I started out in physical training” recalls Veteran Harold Hines. Recruits were required to take mathematics, chemistry, and physics alongside naval classes, including seamanship and navigation.

The advent of the V-12 program also brought with it one of Southwestern’s best-ever football teams. In his memoir, V-12 veteran JC Baumgartner writes, “There wasn’t much exciting around Southwestern except the excellent football team.” In James Schneider’s Naval V-12 Program: Leadership for a Lifetime, Schneider writes, “Thanks to the V-12 program, a contingent of sailors and Marines made Southwestern a football powerhouse in the 1940s.” In 1943, Southwestern defeated the University of Texas in Austin and won the Sun Bowl against New Mexico, finishing the season 10-1-1 and ranked 11th in the final national football poll. Anchored by MVP William “Spot” Collins, a Marine transferred from UT to Southwestern as part of the V-12 Program, the Southwestern Pirates won 7-0 against the New Mexico Lobos. Collins became one of fourteen NFL players to serve in both World War II and The Korean War.

Years later, V-12 Alumni would return for a reunion. Writing on questionnaires they were given, they wrote the names of men they knew had been killed in action. William E Rodney of Baton Rouge wrote of Dick Leon Davis, who was killed on Iwo Jima, in 1945. Douglas F Pollard wrote the name of John Milton Cornelius, who was killed in Okinawa. John Fitzgerald, the marine commander who Marjore Beech wrote “added greatly to our community,” was killed on Iwo Jima.

We often view the men who manned the vessels in the South Pacific, stormed the beaches of Normandy, and rushed through blood and bone on Okinawa as unfathomable titans of history–but their great contributions were made at such a young age. They walked through the same paths you did, maybe they even had a class in the same room you did. They worried about the same things you or I might do, sports, relationships, fraternities, and they put their lives on the line fighting the greatest evils this world has ever seen. It is our charge as students to ensure that future generations must never again make that sacrifice–and that the sacrifices of those before us are remembered. Perhaps that is, over any monument, the best thanks we can offer them.