Review: Many Mini Murder Scenes

Share

A Texas artist and avid reader of mystery novels, Candace Hicks displayed her most recent series, Many Mini Murder Scenes, as a critique on the romanticisation of women’s deaths in fiction literature. Like much of her work, the murder scenes rely on the written word for their inspiration and work to examine inequality in the real world as present in fiction. Her pieces range from dollhouse-like dioramas depicting murder scenes to paper “paintings” that rise out of their frames through careful 3D construction.

When observers walk through the glass doors of the Austin-based art gallery, Women and Their Work, they are immediately presented with a booklet detailing the murder mysteries that Hicks has excavated to create her many scenes. Along with wisecracks comparing a cucumber patch to a certain British actor, the booklet explains the significance of various mystery novels for each piece as the viewer peruses the exhibit. Provided with a UV keychain, the onlooker is invited to shine a literal light into the murder scenes and discover last words, quotes, and quips from the many books that color Hicks’s creations.

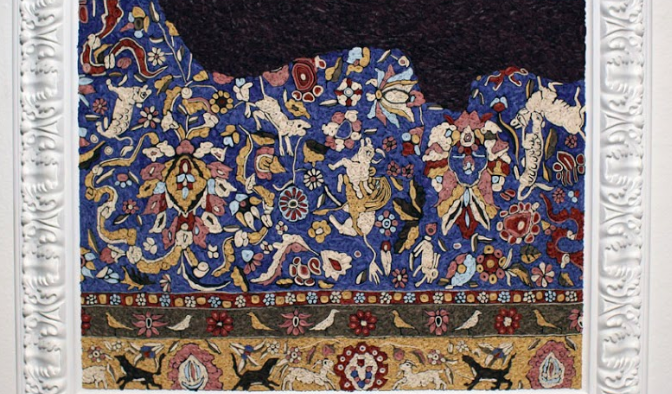

Her hanging work in this installation ranges from a paper bouquet of flowers next to a lifeless crown of hair to a quilled ornamental rug with a creeping bloodstain. The dioramas are no less captivating, including a bachelor pad, hidden stairwells, and a restless canoe on frozen water. The precision that is apparent in each piece is astounding, every edge clean and each leaf placed with care. Beginning in the summer of 2017, this series took almost a complete calendar year for Hicks to complete, demonstrating her patience and dedication to accuracy.

Hicks explains that she wants to make her installation similar to a book in the sense that the viewer brings something of themself to the art. She says that she is not often interested in art that is completed by the artist alone and desires a more collaborative and interactive experience. Viewer engagement is crucial for Hicks’s gallery as onlookers discover secret rooms and hidden words written in the sand and water. Some of the books that Hicks references in her invisible quotations include The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie, The Trespasser, and The Talented Mr. Ripley as common themes, misunderstandings, and fallacies are carefully examined throughout her installation.

Hicks was partly influenced by the works of Frances Glindler Lee, the first female police captain in the United States and creator of the Nutshell series, which uses dolls to depict murder scenes from history. Lee used her artistic skills to create these scenes for forensics students at Harvard University who could then use them to practice detective work without disturbing and possibly ruining a real crime scene. While Hicks holds a great deal of admiration for Lee, she believes the use of dolls has the capacity to dehumanize the victim and depress the audience without creating the artist’s desired impact. Because of this, Hicks chose to omit the bodies and gore from her own work, creating an eerie and uncanny space highlighted by the text hidden in the dioramas.

She was also inspired by a visit to The National Museum of Toys and Miniatures in Kansas City. Hundreds of toys and models ranging from pottery to architecture reflect Hicks’s dedication to detail when constructing each candlestick and paint can for her murder scenes. Although Hicks admits that there can be a slight stigma surrounding so-called dollhouse art, her attention to detail and social awareness expands the field of miniatures into a thoughtful critique and assessment of present day chauvinism.

In addition to the murder scenes’ somewhat morbid surface interest, they have a deeper meaning as well. Hicks uses her art to examine underlying inequalities in the world around us, and the Many Mini Murder Scenes focus specifically on gender and race bias. Hicks explains that although the majority of murder victims in real life are men, murder mystery novels overwhelmingly choose beautiful, young, white women as their victim of choice. She also notes that this is by no means a new phenomenon. Nineteenth century writers such as Edgar Allan Poe are infamous for their use of female death to kickstart a short story. In this way, female gendered violence is more common in entertainment that in fact even as fiction and reality influence each other in interesting ways. Hicks cites some of this thinking from Maggie Nelson’s literary works, including The Art of Cruelty, The Red Parts, and Jane: A Murder. The romanticisation of women’s deaths has far-reaching implications in our world, especially because the consumers of this brand of literature are mostly female.

Candace Hicks has created a stunning installation of paper paintings and dioramas that simultaneously evoke unsettling feelings of hidden violence while unearthing the delight of discovery. Utilizing countless materials, Hicks’s murder scenes demonstrate supreme precision while never losing sight of a higher message. An informed statement on social discrimination and bias, the Many Mini Murder Scenes are an engaging work that its viewers will not soon forget.